Jeremiah Denton

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Jeremiah Denton | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator | |

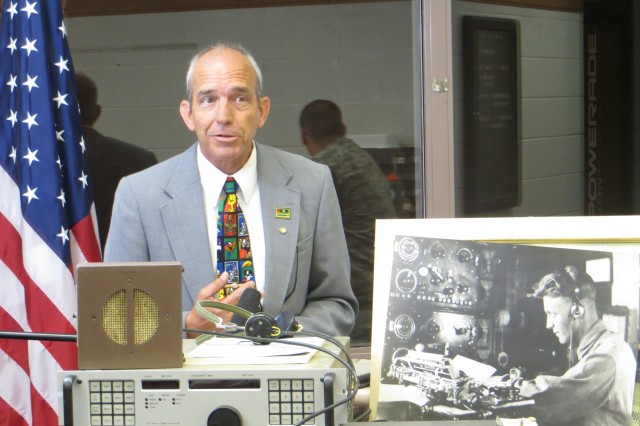

Ten months into his confinement (1965-1973) as one of the highest-ranking officers to be taken prisoner in Vietnam, Denton was forced by his captors to participate in a 1966 televised propaganda interview, broadcast in the United States. While answering questions and feigning trouble with the blinding television lights, Denton blinked his eyes in Morse code, spelling the word "TORTURE" — and confirming for the first time to U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence that American POWs were in fact being tortured.

In 1976, Denton wrote When Hell was in Session about his experience in captivity, which was made into the 1979 film with Hal Holbrook. Denton was also the subject of the 2015 documentary Jeremiah produced by Alabama Public Television.